In the first part of this series, we explored the theoretical foundations of our study, examining the complex relationship between social media (SM) use, peer norms, and adolescent well-being. Now, we’re excited to share the findings from our research, conducted in collaboration with the University of Padova.

This study aimed to address a critical gap in the literature: the role of social context in shaping the relationship between SM use and well-being. By analyzing data from a representative sample of Italian adolescents, we investigated how different social media behaviors—time spent on SM, problematic social media use (PSMU), and SM communication—interact with classroom norms to influence social well-being.

First of all, our results align with previous research, showing that SM can have both positive and negative effects on well-being [1]. However, what sets this study apart is its emphasis on the moderating role of social context. Classroom norms emerged as a key factor influencing how SM use impacts adolescents’ social well-being.

Our first hypothesis focused on the relationship between time spent on SM and well-being. We found that, at an individual level, spending more time on SM was weakly associated with lower class support and higher loneliness. This supports the displacement hypothesis, which suggests that excessive time online can detract from in-person social interactions.

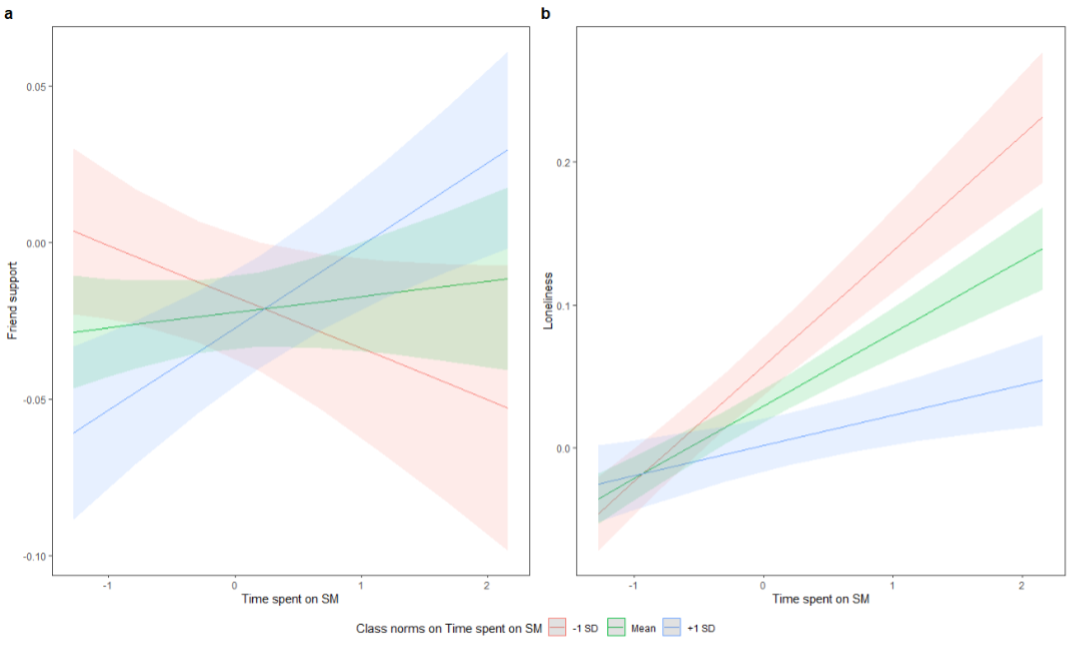

However, the story changes when we consider classroom norms (Fig. 1). In classes where high social media use was the norm, adolescents who spent more time online reported higher social well-being. This finding aligns with the normalization theory, which posits that behaviors typically considered “risky” may have less negative impact in contexts where they are widely accepted. That said, the effect sizes were small, echoing previous research that questions the practical significance of screen time alone [2]. This underscores the importance of looking beyond mere time spent online and examining how SM is used.

Our second hypothesis examined the impact of problematic social media use (PSMU), characterized by addiction-like symptoms such as salience, mood modification, and withdrawal. Across all dimensions of social well-being, PSMU was associated with worse outcomes. Adolescents with high PSMU often prioritize their devices over real-world interactions, and this could lead to lower social support.

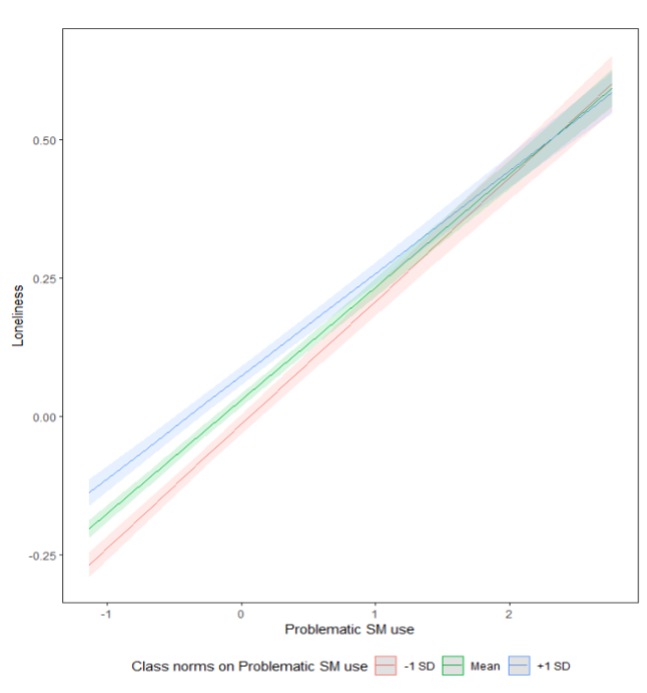

Interestingly, classroom norms played a moderating role here as well (Fig. 2). Adolescents with low PSMU symptoms reported higher loneliness if they belonged to classes with higher average PSMU. This suggests that PSMU doesn’t just affect the individual; it can also shape the social dynamics of the entire group. For instance, adolescents struggling with PSMU may be less able to provide a supportive social network for their peers, contributing to a broader sense of isolation.

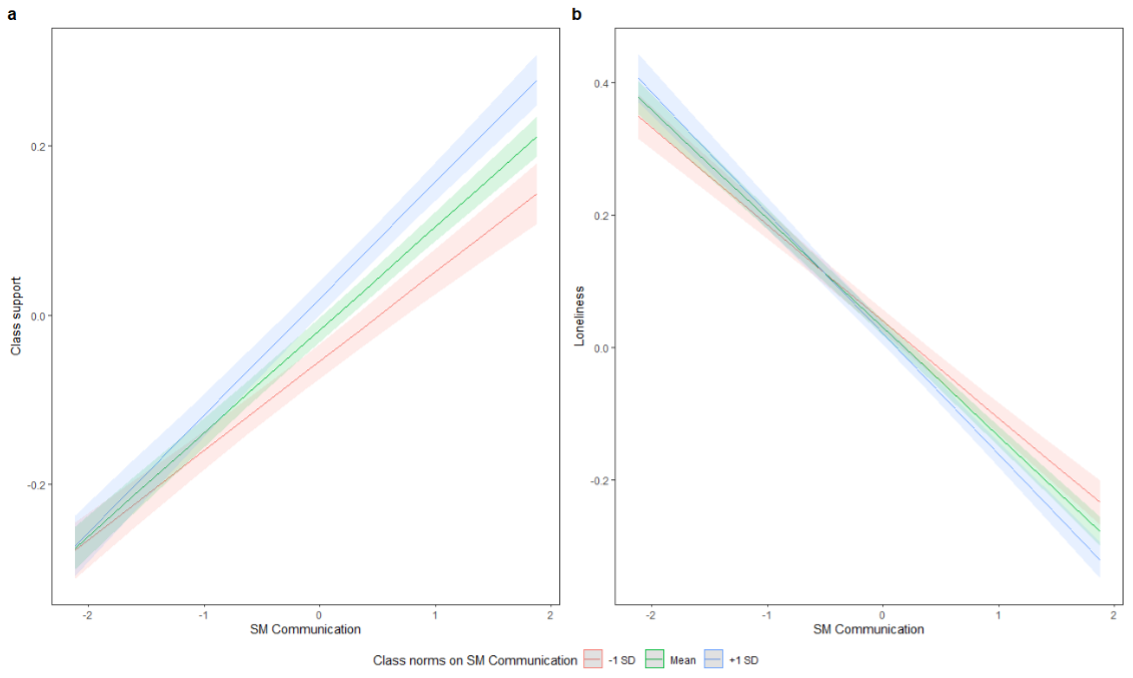

Our third hypothesis focused on SM communication, which involves active, reciprocal interactions with others. Consistent with the extended active-passive model of social media use [3], we found that social media communication was associated with better social well-being across all dimensions. Adolescents who used SM to communicate with friends reported higher class support and lower loneliness, especially in classes where such behavior was common (Fig. 3).

This finding aligns with the media multiplexity theory, which suggests that strong relationships are often maintained through multiple communication channels [4]. For many adolescents, social media serves as a complement to offline friendships, enabling them to stay connected regardless of time or space constraints.

Like any study, ours has its strengths and limitations. On the positive side, the consistency of our results across different methodologies and school years underscores the robustness of our findings. Additionally, the medium-to-large effect sizes for PSMU and SM communication highlight the importance of studying these behaviors separately, rather than lumping them under the umbrella of “screen time”.

However, there are limitations to consider. The cross-sectional nature of our data prevents us from establishing causal relationships. For example, it’s possible that adolescents who lack offline support turn to social media as a coping mechanism, rather than social media use causing loneliness. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore these dynamics further. Additionally, our reliance on self-reported measures may introduce biases, particularly when estimating time spent on social media. Future research using objective measures would help validate these findings. Finally, while our sample was large and representative of Italian adolescents, the results may not generalize to other cultural contexts.

The findings from this study, based on data from over 70,000 Italian adolescents, underscore the dual nature of social media. On one hand, when used responsibly, social media can enhance and complement offline relationships, fostering connection and support. On the other hand, problematic use can lead to isolation and lower well-being, particularly in contexts where such behavior is uncommon.

From a practical perspective, these results highlight the importance of social norms in shaping adolescents’ experiences with social media. Parents and educators should consider the broader social context when setting rules around social media use. For example, decisions about when adolescents get their first social media account should ideally be coordinated within the community to ensure consistency and promote healthy peer integration. Initiatives like Patti Digitali [5] in Italy, which encourage collaborative approaches to digital parenting, offer promising examples of how this can be done effectively.

As social media platforms continue to evolve - shifting from spaces for interaction to entertainment-driven environments focused on user retention - it’s more important than ever to help adolescents navigate this complex landscape. By understanding the role of social context and promoting responsible use, we can empower young people to harness the benefits of social media while minimizing its risks.

1. Pouwels JL, Beyens I, Keijsers L, Valkenburg PM (2024). Changing or stable? The effects of adolescents’ social media use on psychosocial functioning. Child Development n/a.

2. Orben A, Przybylski AK (2019). Screens, Teens, and Psychological Well-Being: Evidence From Three Time-Use-Diary Studies. Psychol Sci 30:682–696.

3. Verduyn P, Gugushvili N, Kross E (2022). Do Social Networking Sites Influence Well-Being? The Extended Active-Passive Model. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 31:62–68.

4. Haythornthwaite C (2005). Social networks and Internet connectivity effects. Information, Communication & Society 8:125–147.

5. Patti Digitali (2024). https://pattidigitali.it/. Accessed 27 Dec 2024